By Mitch Bogen

We are at the beginning of a great adventure,” said Harvard University’s Nur Yalman near the conclusion of the Ikeda Center’s September 2011 seminar exploring themes from Daisaku Ikeda’s September 1991 Harvard University address, “The Age of Soft Power.” Professor Yalman was describing both the pace of change in our rapidly globalizing world and the urgent challenge of activating globally what Mr. Ikeda described in his address as “the inner resources of energy and wisdom existing within our lives.” For Ikeda, these inner resources constitute the primary tools of soft power. In contrast, the tools of “hard power” are coercive in nature.

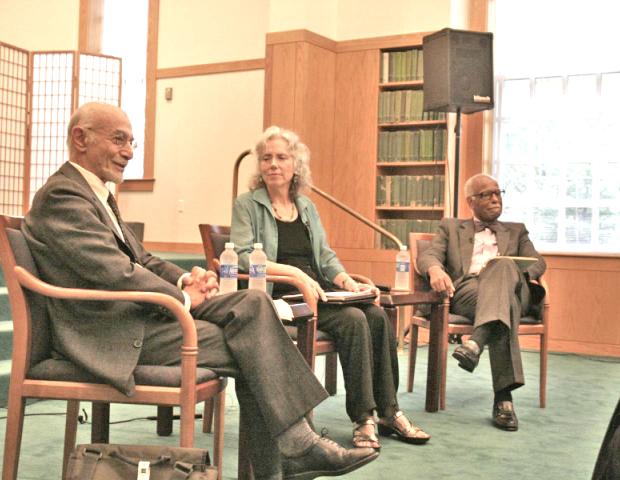

Professor Yalman, who is professor of Social Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies at Harvard, was joined as featured seminar discussant by Winston Langley, Provost and Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Both scholars have in recent years engaged directly with Mr. Ikeda on important matters of peace, education, and cross-cultural understanding. Yalman’s dialogue with Ikeda, A Passage to Peace, was published in English in 2009. In late 2010, Langley was part of a delegation from U-Mass Boston that traveled to Tokyo to present Mr. Ikeda with an honorary doctoral degree. Because of these personal connections both flavored their analysis of the lecture with warm impressions of the SGI president, whom they regard as someone whose efforts toward peace building are admirably comprehensive in conception and implementation.

In planning the event, Center president Richard Yoshimachi and events manager Kevin Maher decided that the best way to honor President Ikeda on the occasion of his lecture’s 20th anniversary would be to invite Boston-area university students to participate in the discussion. Representing schools such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, and with areas of study ranging from engineering to anthropology, the fourteen attending students were united in their optimism and enthusiastic interest in Ikeda’s vision of peace.

The Ikeda Center’s senior research fellow, Virginia Benson, moderated the two-hour seminar. In the first hour, Yalman and Langley responded to her questions and each other’s insights. During their comments, both drew distinctions between Ikeda’s vision of soft power and that of Harvard’s Joseph Nye, who introduced and first explored the influential concept in his 1990 book, Bound To Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. Professor Nye was a respondent when Mr. Ikeda delivered his Harvard soft power address the following year.

Langley explained that because Nye’s experience includes positions in the US State Department, Nye, like others in positions of governmental authority, pragmatically holds hard power “as a contingency”—even as he urges greatly expanded reliance on soft power. Ikeda, of course, is not a foreign policy analyst or governmental official; rather, said Langley, his objectives often are educational and spiritual, aimed at the “the transformation of individuals.” Without this inner transformation, he continued, institutional efforts at peace building will never succeed. Yalman added that Ikeda’s conception of soft power is based a desire to speak “directly to people’s hearts.” Langley concurred, observing that each of us contains “an inner universe,” which, if consciously explored, gives rise to “a respect for other human beings.”

Shifting to the collective level, Yalman indicated his respect for Ikeda’s ability to build an international institution—Soka Gakkai International—”devoted to the message of peace.” He also appreciated Ikeda’s institutional support for the United Nations as an agent of soft power. Among the great achievements of the UN in recent years, said Langley, was UN Security Resolution 1325, passed in the year 2000. This resolution, he explained, stated that women should not be seen as “objects of concern” but rather as active participants in worldwide efforts toward peace, security, and the management of conflict. Including women in this way represents an important dimension of soft power, Langley said.

Two other key points emerged during Yalman and Langley’s discussion, which addressed not only Ikeda’s lecture but also his broader philosophical vision. Especially noteworthy, Langley said, is how Ikeda revives a form of humanism based on “broad faith in human possibilities.” This faith provides a necessary foundation for the interpersonal and intercultural dialogue that Ikeda sees as the surest path to peace. The other foundation for meaningful dialogue, said Yalman, is one that Ikeda consistently champions, namely the human capacity for empathy.

The second half of the seminar was devoted to students engaging directly in dialogue with the professors on ideas that arose during the first hour. Among the most heartfelt questions were those addressing the sometimes-discouraging challenge of spreading humanistic philosophy fast enough to offset the conflicts sparked by the rapid pace of finance- and technology-driven globalization.

Undoubtedly, said Langley, “transforming the human spirit remains the more difficult task.” Responding to a question about technology’s importance to the “Arab Spring,” he agreed that new technology enhances communication, but underscored that it is our “moral consciousness” that ultimately determines whether or not technology will contribute to the development of humanity. The moral authority of those rebelling against oppressive regimes, he said, is derived not from technology but from “certain broad categories of human rights.”

Yalman and Langley agreed that pursuing the path of soft power requires patience and an ability to live with a degree of uncertainty as to what our global future might hold. Nevertheless, said Yalman, and despite the difficulty of the task, “we all must strive” for a peaceful world built on humanistic principles and truths such as those put forth in Ikeda’s soft power address. High among those truths, Langley, Yalman, and the students agreed, is that of what Buddhists call dependent origination and what is understood more generally as the interrelationship of all life.

As the end of seminar drew near, Professor Yalman emphasized that Mr. Ikeda’s focus on the inner growth of individuals is an example of the kind of “universal values” that can help connect people across religions and philosophies. “I think that there is hope there,” he concluded. “Let us try and bring it about.”