On Thoreau: "Refusing All Accustomed Paths"

Here, we are reprinting an excerpt from Conversation Four of Creating Waldens: An East-West Conversation on the American Renaissance, by Ronald A. Bosco, Joel Myerson, and Daisaku Ikeda, published by Dialogue Path Press in 2009. This excerpt explores Thoreau’s constant self-invention and his evolving relationship with his mentor, Ralph Waldo Emerson.

IKEDA: Thoreau spent almost his entire life in Concord. The name Concord refers to the peaceful negotiations through which the colonists obtained the land from the indigenous people. Of the river flowing through town, Thoreau wrote, “It will be Concord River only while men lead peaceable lives on its banks.” (1) Concord was then a prosperous country town with a population of less than two thousand, mostly farmers. But idealistic intellectuals like Emerson lived there, too, creating a cultural ambience more stimulating than anywhere else in America.

BOSCO: In a journal entry dated December 5, 1856, Thoreau described his life and his delight in having been born in the first half of the nineteenth century and been a citizen of Concord: My themes shall not be far-fetched. I will tell of homely every-day phenomena and adventures… . I have never got over my surprise that I should have been born into the most estimable place in all the world, and in the very nick of time, too. (2)

The enthusiasm with which Thoreau described his life as the pursuit of “homely every-day phenomena and adventures” is genuine, as is the sense of joy with which he expressed his belief that he was “born into the most estimable place in all the world, and in the very nick of time.”

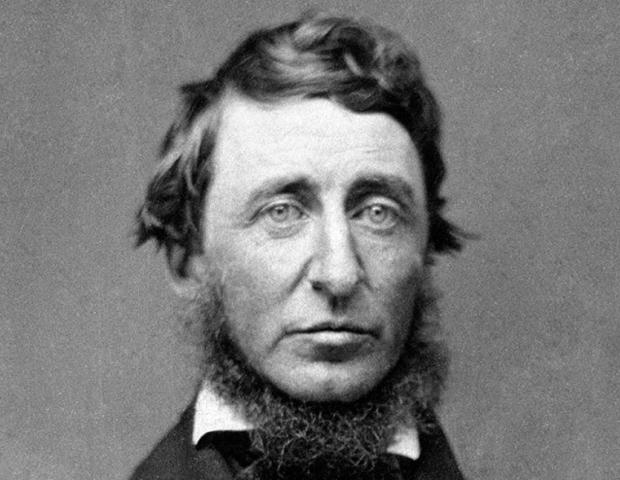

IKEDA: When Thoreau was born in 1817, the Revolutionary War was a thing of the past, the Civil War yet to come. His youth was spent in a happy place at a happy time.

BOSCO: His biographers have always found it difficult to name him or define his character through conventional pronouncements such as “Thoreau was a… .” Over the course of his forty-four years, Thoreau was variously a teacher and tutor; a lecturer on the lyceum circuit; an author and literary naturalist; an abolitionist and political reformer; a philosopher; an environmentalist; a sojourner at Walden Pond; and an explorer of Concord’s rivers, the Maine Woods, and Cape Cod. Defining Thoreau’s life or character through reference to only one or a combination of only some of these activities does severe disservice to the range of his intellectual interests and imaginative expression, and certainly diminishes the profound impact his life and thought have exerted on American culture—indeed, on global culture—over the century and a half since his death.

IKEDA: Again, it is wrong to reduce any human being—especially a versatile one like Thoreau—to a single characteristic. In many ways, Thoreau’s life itself is even more appealing than his written works.

He reminds me of Gandhi, who, when asked what his message was, replied, “My life is my message.” (3) Had Thoreau been asked a similar question in his later years, he probably would have had the same response. His entire life was one wonderful literary work.

BOSCO: Thoreau’s most straightforward explanation for his life and character comes at the conclusion of Walden, where he explains his reason for leaving the pond. Believing he had more than one life to lead, he felt he could spare no more time on that one.

IKEDA: Tracing Thoreau’s life, one finds new challenges, new discoveries, and new progress at each stage. As Emerson said in his eulogy for his friend, Thoreau refused “all the accustomed paths.” (4)

And in Walden, he alluded to the Confucian classic Daxue, advising that one should renew oneself daily and completely, and go on doing so over and over, never losing enthusiasm. (5) Thoreau’s writings are a guide to his struggle to live in the exceptional way he chose.

MYERSON: They record the extraordinary accomplishment of an individual who, to paraphrase his own words, lived deep and sucked out all the marrow of life. A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) recreates an excursion he took with his brother John in 1839; Walden reports the insights he gained while living at Walden Pond between July 4, 1845, and September 6, 1847.

IKEDA: These are his only works published during his lifetime.

MYERSON: The Maine Woods, published in 1864, two years after his death, recounts his three expeditions to the Maine wilderness between 1838 and 1857. Cape Cod, published in 1865, describes his four walking tours across that prized New England landscape between 1849 and 1857.

BOSCO: The fourteen volumes of his journal, which Thoreau began in 1837 at the suggestion of Emerson, preserve the spontaneity, originality, and depth of his observations of and reflections on all that he saw and felt during the twenty-five-year span these volumes record.

IKEDA: In the following lovely verse, Thoreau expressed his eagerness to plumb all life’s possibilities: “My life has been the poem I would have writ / But I could not both live and utter it.” (6) All of his philosophy is revealed in his journal, which provided the basis for his essays and lectures.

BOSCO: A host of essays, many of them drawn from lectures but published only after his death, establish Thoreau as America’s premier patriot and social critic, her earliest prophet of the advantages of a life lived wholly in concert with nature, and her most influential proponent for the preservation of the natural environment.

IKEDA: He was ahead of his time in discussing many of the problem areas—the environment, mass culture, human rights, the media— that the whole world is facing today. Indeed, timely observations on all these topics are to be found throughout his work.

Although all his writing is compelling, he is especially brilliant on nature, combining scientific and spiritual observations, high literary and ethical standards, and—most inspiring of all—his love for the natural world and respect for life.

MYERSON: For their blending of science with acute observation,“The Succession of Forest Trees” (1860) and the lyrical “Autumnal Tints” (1862) are two noteworthy examples of his natural-history writings.

IKEDA: He also wrote sharp criticisms on societal contradictions. We find in his works expressions of anger against human arrogance, social evils, and injustice.

BOSCO: He harshly criticized slavery in “Slavery in Massachusetts” (1854) and in “Life Without Principle” (1863). In 1859, he wrote “A Plea for Captain John Brown” in defense of the abolitionist John Brown, who was arrested and hanged for raiding an arsenal and armory.

In these three works, he developed some of his most passionate and sustained arguments against capitalism; the inhumanity of the institution of slavery; the perfidy of governments that suppress individual conscience; and the shame of those who, knowing better, fail to heed the dictates of individual conscience.

IKEDA: In “Slavery in Massachusetts,” for example, Thoreau wrote: “The law will never make men free; it is men who have got to make the law free. They are the lovers of law and order, who observe the law when the government breaks it.” (7)

Thoreau, a man to whom contradictions in society were perfectly clear and deserving of criticism, looked down upon political authority from a spiritual height.

BOSCO: Walden is unquestionably Thoreau’s masterpiece, but had he written no more during his life, “Civil Disobedience” (1849) and“Walking” (1862) would have guaranteed his reputation throughout the ages. “Civil Disobedience” has directly inspired such momentous cultural transformations as the nonviolent revolution led by Gandhi in India; the civil rights movement led by King in the United States; and the global peace movement led by you, President Ikeda. “Walking,” along with Walden, has inspired numerous champions of environmentalism, including Rachel Carson, John Muir, Edward Abbey, and Annie Dillard.

IKEDA: Thoreau’s works inspire in us the will to live. Beyond being classics, they can inspire today’s youth with the courage of this nineteenth-century American idealist. I hope that, inspired by the great lessons of his life, large numbers of twenty-first-century Thoreaus will emerge to smash stereotypes and live their lives freely in their own ways.

After graduating from the Concord Academy at sixteen, Thoreau entered Harvard College. Disliking the emphasis on rote memorization, he spent his time in the library reading on his own. Preferring self-study, he seems to have assimilated naturally the principles Emerson propounds in “Self-Reliance.”

BOSCO: Although he received the classical education proper for his time and place at Harvard during the 1830s, it is undeniably the case that his real education took place in the company of Emerson and in the woods, meadows, waterways, and fields surrounding the Concord that Thoreau loved.

IKEDA: Nothing contributes to a young person’s growth like encounters with great human beings. Meeting my mentor when I was nineteen is the greatest happiness of my life. He always told me: “Do everything you can to meet great people, even if you can only listen to them from afar. This is the supreme form of education and a great gift to yourself.”

Great people are living models of the possibilities inherent in human life. Association with them stimulates the desire to emulate them and the confidence that you can. A great soul is the greatest inspiration. Such encounters help us develop more than a thousand books would. Thoreau was twenty when he first met Emerson, in the autumn of 1837, the year he graduated from Harvard.

BOSCO: Since the nineteenth century, scholars have been fascinated by and debated the nature of the relationship between Emerson and Thoreau. Surely, it began as a mentor-student relationship.

In the late 1830s, just as Thoreau was completing his studies at Harvard, he not only read Emerson’s Nature but also came into close personal contact with this great man. From my viewpoint, that Thoreau developed a close relationship with Emerson makes perfect sense and in no way detracts from the originality of Thoreau’s ideas and writing.

IKEDA: Not in the least. Thoreau was always more than Emerson’s follower.

BOSCO: Emerson was, after all, Thoreau’s elder; he was an extraordinarily well-read and even world-traveled man by the time Thoreau met him. He was the “idea man” for Thoreau’s generation; and certainly in the early years of their relationship, Emerson piqued Thoreau’s intellect and imagination with ideas and theories that the youthful Thoreau tried to put into practice, like following Emerson’s practice of keeping a journal.

IKEDA: While he was acting on Emerson’s ideas and theories, Thoreau developed and deepened his own thought. Ultimately, he became a soaring philosopher in his own right.

MYERSON: The concept of a mentor-disciple relationship as regards Emerson and Thoreau is a complicated one. Surely, in the beginning, Thoreau would have responded to Emerson as a mentor, but I think Thoreau would have defined disciple as a person in progress.

IKEDA: In “The American Scholar,” Emerson said that ideas without action can never become truths bearing mature fruit. Thoreau was better at applying ideas. His learning from Emerson stimulated enough growth in his own philosophy to startle Emerson. Perhaps this was only natural.

BOSCO: The mentor-disciple relationship that started in the late 1830s grew into deep friendship in the 1840s. Here I think we must distinguish between mentorship—if you will—and friendship.

IKEDA: The relationship grew into one in which the two men learned together. In 1841, when Emerson invited Thoreau to join him in dialogue aimed at growing wiser together, Thoreau moved into the Emerson house, where he took on various domestic tasks.

In a letter to his friend Thomas Carlyle, Emerson described Thoreau as a “noble, manly youth, full of melodies and inventions.” (8) He had great respect for Thoreau, whose development delighted him.

BOSCO: By the time Emerson and Thoreau had become friends— throughout the 1840s, that friendship taking the form of Thoreau’s temporary membership in Emerson’s household and its extended family—Thoreau had moved significantly beyond what Emerson could offer as his mentor.

In his essay on “Experience,” Emerson provided us with an important clue as to how that mentor-disciple relationship could easily have ended and been replaced by friendship. Emerson wrote that the world outside his study window—the everyday world of real men and real women—is not the world “I think.” This is Emerson’s confession of his personal disposition toward theory in preference to practice.

Thoreau, on the other hand, seems to have made a concerted effort to erase any distinction between the world he thought and the world he enjoyed in the natural environment in and around Concord.

IKEDA: For Emerson, nature was abstract; for Thoreau, it was concrete— to be seen with the eyes, heard with the ears, and touched with the hands. In his journal, Emerson praised Thoreau’s use of brilliant images to explain ideas that could have become tedious.

BOSCO: It was not that, having become friends, Emerson and Thoreau had nothing left to learn from each other. The nature of their relationship had undergone a dramatic and fundamental change.

MYERSON: Throughout the 1840s, many people remarked on the physical similarities—particularly of their noses—as well as the intellectual similarities between Emerson and Thoreau. It was almost always assumed that Thoreau borrowed his ideas from Emerson. This eventually began to grate on Thoreau and was no doubt a significant factor in the estrangement the two men felt in the 1850s.

BOSCO: Thoreau had become his own man and, even by Emerson’s admission later in life, had much to teach his former mentor. In his lecture “Country Life,” which he first delivered in Boston in 1858, Emerson, without naming him, revealed his reliance upon Thoreau as his foremost “professor” of nature. In allusion to Thoreau, Emerson wrote that it is better to learn the elements of geology, of botany, of ornithology and astronomy by word of mouth from a companion than dully from a book. There is so much, too, which a book cannot teach which an old friend can. (9)

IKEDA: Emerson urged people to learn from nature. Then he found himself in the position of learning a great deal from Thoreau, who himself had learned many things through immersion in nature. Doesn’t this reflect Emerson’s view of how the mentor-disciple relationship should be?

BOSCO: In his essay “Poetry and Imagination,” Emerson states that the highest calling of the poet is to teach his reader to despise the poet’s song. (10) By this, he means that we all have the capacity to be poets, but maybe only now and then a great person comes along to inspire and move us to look to our own ability within—and eclipse eventually the poet and the poetry that once inspired us.

This is how I believe Emerson looked at the mentor-disciple relationship generally and how he regarded his relationship with Thoreau specifically. Emerson believed that it was to Thoreau’s credit that he moved out from under the shadow of the great man.

IKEDA: A mentor wishes his disciples to go beyond the mentor and develop on their own. In the relationship as it should be, the mentor wants to stimulate his disciples to stride ahead on the strength of their own ideas and actions.

BOSCO: I believe that is exactly what all teachers and mentors should hope for regarding their students. In my case, I have been privileged to have been taught by some of the finest men and women I have ever met.

The natural evolution of the mentor-student relationship has been for the student eventually to move beyond the mentor. All the doctoral candidates I have prepared have been exceedingly fine students. Whatever fields they are working in or whatever they are writing about, they are now serving me as mentors; I am learning much from them that is new to me.

IKEDA: Nothing pleases me more than the development and triumph of young people. That is my major reason for devoting myself to educating youth.

In a deeply moving funeral oration, Emerson, who knew Thoreau’s greatness better than anyone, said that his friend’s soul was created for the noblest exchanges. In society today, this kind of mentor-disciple relationship—a relationship of noble exchanges— is on the wane. Its weakening lies at the heart of our many youth-related problems.

I am not talking about a unilateral, suppressive, superior-inferior relationship but a creative partnership transcending generational differences. It might be described as progressive comradeship, in which both sides mutually inspire each other while moving toward the shared goal of heightened humanity.

I hope we can give new life to the beautiful bonds of friendship and wonderful interactions of which human beings are capable, as did Emerson and Thoreau in their mentor-disciple relationship.

Notes

1. Henry David Thoreau, A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, in A Week, Walden, The Maine Woods, Cape Cod, ed. Robert F. Sayre (New York: Library of America, 1985), p. 7.

2. The Journal of Henry D. Thoreau, ed. Bradford Torrey (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1906), 9:160.

3. Mahatma: Life of Gandhi 1869–1948, video by Vithalbhai Jhaveri (The Gandhi National Memorial Fund in cooperation with the Films Division of the Government of India, 1968), Reel 31.

4. Emerson, “Thoreau,” in Essays and Poems, eds. Joel Porte, Harold Bloom, and Paul Kane (New York: Library of America College Editions, 1983), p. 1009.

5. Thoreau, Walden, in A Week, Walden, The Maine Woods, Cape Cod, p. 393.

6. Henry David Thoreau, Collected Essays and Poems, ed. Elizabeth Hall Witherell (New York: Library of America, 2001), p. 552.

7. Ibid., p. 338.

8. Emerson to Carlyle, May 30, 1841, in The Correspondence of Emerson and Carlyle, p. 300.

9. Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Concord Walks,” in The Complete Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson, vol. XII (New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1903–04), p. 176.

10. Ralph Waldo Emerson, “Poetry and the Imagination,” in Vol. VIII—Letters and Social Aims, at “The Works of Ralph Waldo Emerson” website: www.rwe.org