Ikeda Center Convenes Inaugural Educating for Peace Conference

The Ikeda Center’s inaugural teachers’ conference for nuclear disarmament education was a two-day event held on May 10 and 11, 2025. Called “Educating for Peace,” the conference was co-organized with the Soka Institute for Global Solutions (SIGS) at Soka University of America, the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, and EdEthics at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE). As everyone gathered that Saturday morning, spirits were high following the successful panel discussion on the topic held in Askwith Hall at HGSE the previous evening. The mood was also optimistic because the inaugural conference represented the realization of a dream born exactly one year earlier when the Ikeda Center hosted a one-day forum on nuclear disarmament education. It was there that the idea of bringing together educators and peacebuilders on a regular basis to advance nuclear disarmament education first took shape.

Ikeda Center Executive Director Kevin Maher shared in his opening remarks his hope that “ten years down the line” this group can look back to this moment as the starting point of building a network of educators committed to creating a world free of nuclear weapons through education. Maher concluded his remarks with a quote from Center founder Daisaku Ikeda’s essay, “Our Power for Peace,” which was published in the book Hope In a Dark Time, edited by the late David Krieger, who was the founder of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation.

I firmly believe that peace education—education that stirs empathetic imagination by conveying the realities of war—is our shared responsibility. All sectors of society, the schools, the media and religious institutions, can play a part. In particular, I hope that young people will learn never to be deceived by sanitized or glorified portrayals of violence and war.

The limitless power of the individual is unleashed when we work together. This is the power of connection, the power of human solidarity. Our dreams grow and flourish when we speak them out loud, when we share them with others. To do this requires courage. We must overcome the fear that we will be misunderstood, looked down on or laughed at for putting into words the content of our hearts.

Tetsushi Ogata, Managing Director of SIGS, also shared remarks. Echoing the long-term vision shared by Maher, Dr. Ogata expressed his wish that this group will continue to gather next year, in three years, in five years, and beyond. “Then in 2045, 20 years from now, we can come back and celebrate the centennial anniversary of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, having abolished nuclear weapons,” said Ogata. He concluded with this sentiment: “The beginning always starts from somewhere, and it’s here.”

Day One Activities

After the welcoming remarks, the day’s activities commenced with a goal setting activity in which each participant identified one thing they hoped to come away from the conference with. Responses largely fell into one of four categories. The first was to take away something concrete, such as the educator who hoped to increase their specific knowledge of the issue and use it to create nuclear disarmament activities and a project for 10th/11th grade students. Several others hoped to create connections and networks for collaboration. As one put it, “I am eager to learn how the Center can support forming a network of educators committed to nuclear disarmament.” Another said their goal is to “create a civil engagement movement amongst our students” and to “promote critical thinking skills focused on values that concern us all.” The third category noted the challenge of this sort of education, with one stating that they want to “learn how to communicate difficult topics to young people in a way that encourages action.” The final category was represented by one participant’s desire to “unite with everyone for the people, planet, and future.”

Day One Morning Sessions

The opening conference session was led by Dr. Ira Helfand, a member of the International Steering Group of the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). A true stalwart of the global nuclear disarmament movement, he is a frequent collaborator with the Ikeda Center and SIGS. For his presentation, he shared three essential messages that inform all his talks: First, that nuclear war can indeed happen and cannot be considered at all unlikely; second, that today’s nuclear weapons are far more powerful than those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and their use would be far more catastrophic; and third, that achieving full nuclear disarmament is achievable and not beyond our capacities. Indeed, these weapons are not a “force of nature.” They were created by humans and can be dismantled by them. His talk also included some practical steps that teachers, students, and members of the public can take within their local communities to promote and support nuclear disarmament.

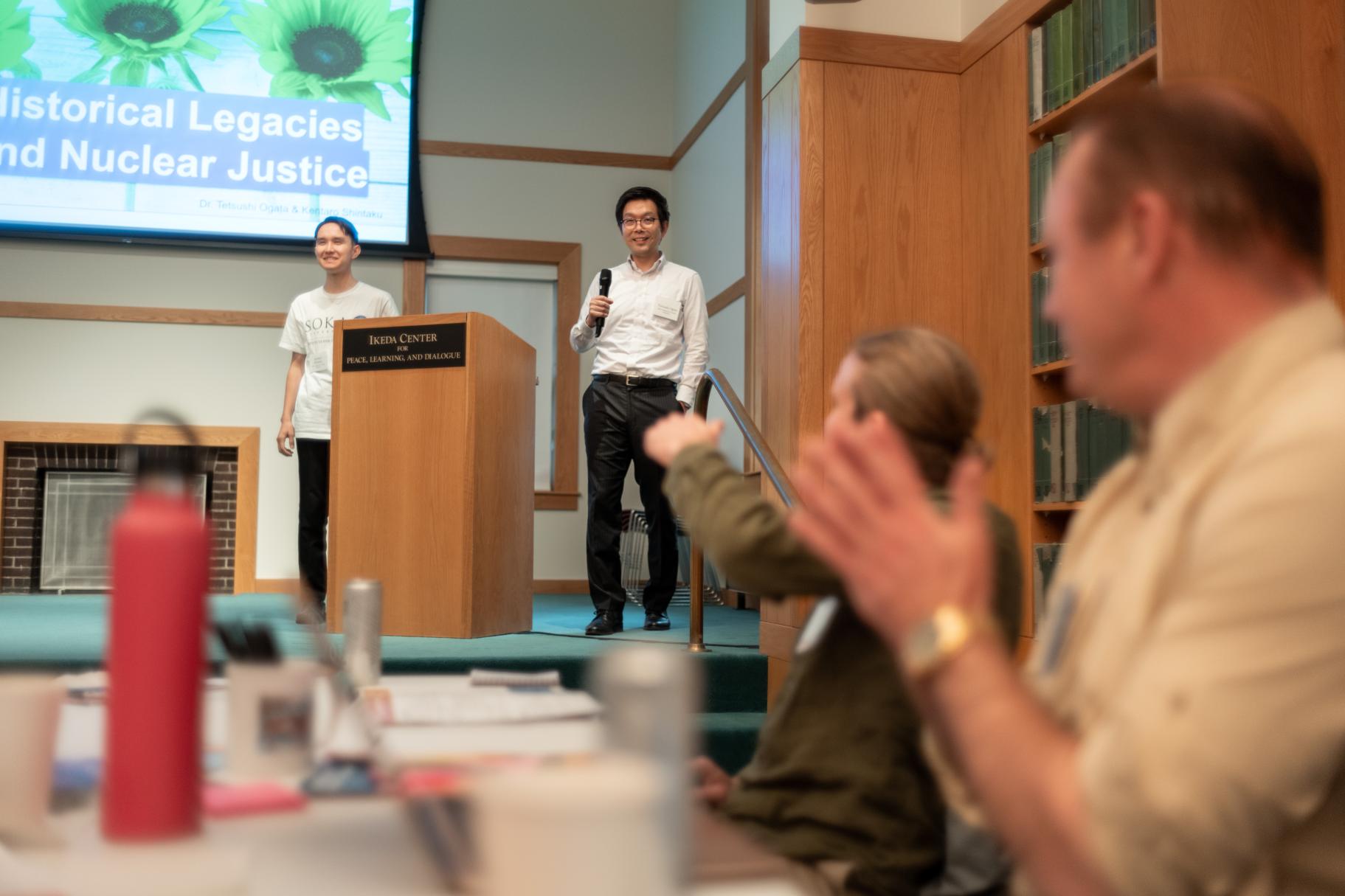

Next, Ogata and Kentaro Shintaku, also from SIGS, gave the presentation: “Historical Legacies and Nuclear Justice.” While Hiroshima and Nagasaki are remembered and taught, rarely do students learn about the extensive nuclear testing carried out by the US in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean from 1946 to 1958. From the US perspective the amount of fallout from the tests was acceptable, and the areas where detonations took place were expendable, thus illustrating one connection between racism and the nuclear legacy. They also shared prime examples of close calls where nuclear conflict was narrowly avoided, another topic rarely taught. In fact, a journalist uncovered declassified US military documents showing that there have been hundreds of such close calls in the US over the last few decades. Thirty-two have been officially recognized by the US, while much less is known about the close calls in other nuclear countries.

Ogata highlighted some of these incidents, including the one in October 1972 when a Soviet B59 submarine in the Caribbean received a signal to come up to the surface. However, the Soviets mistook that message as a war breaking out. Without access to any clarifying information, two of the three officers on board who could make the decision to launch a nuclear torpedo agreed to fire, but one officer said no. If it were not for him, they would have launched a nuclear attack. Another example included a more recent event in Jan 13, 2018, when all residents in Hawaii received an emergency alert stating that there were incoming ballistic missiles, widely assumed to be from North Korea. It was not until 38 minutes later when the alert was revoked, clarifying that the alert was due to human error. In any of these instances, our “spotless” record of nuclear weapons safety would have been instantly nullified, said Ogata. He ended with the emphasis that though we haven’t had a nuclear war in the last 80 years, when we look at the historical information, it’s not accurate to attribute that success simply to deterrence. Rather, he said, “It has been sheer luck that we are surviving today.” Teaching about these historical facts in the classrooms, said Ogata and Shintaku, can help students both understand the reality of our situation today and be better equipped to take action towards building a safer world.

Session three, titled “Integrating Nuclear Disarmament into Existing Curricula” featured two presentations. The first, from Sue Wilkins and Mel Mahoney Bissell of the Boston public television station WGBH. They are developers on the GBH Learning Media resource, “Teaching the Nuclear Age: Past and Present.” Their site is rich with videos, interactive lessons, lesson plans, factual and primary source documents, and highly-accessible graphics. One thing that students and teachers find as they start to engage with disarmament issues is that they are a great many factual matters that come into play, ranging from technical terminology to relevant organizations to all the international resolutions and policies that have been passed or have been under consideration. The GBH site is very comprehensive and makes it possible for students and teachers to get the lay of the land while also engaging in important debates, such as the central one of the deterrence value of nuclear weapons.

The second presentation was by Masako Toki of the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey. During her remarks she introduced one of their key programs, the Critical Issues Forum (CIF), which launched in 1997 and is funded by the US government and the US Department of Energy. CIF is a nonproliferation and disarmament education program for high school students, initially intended for American and Russian students, but which more recently includes Japanese, Indian, and Pakistani students. (Currently, Russian schools are not participating.) The program helps to develop critical thinking and cross-cultural communication skills by bringing students from different backgrounds together to learn about nuclear issues and raise awareness of international peace and security issues. Each year, a topic is chosen related to nuclear disarmament, and teachers participate in an online teacher’s workshop. For example, in 2023 the topic was “Bringing Intersectional Approaches to Youth Education for Nuclear Disarmament and Nonproliferation” With each year’s topic as a guide, each school works on a research project to be presented at a spring conference, which includes both online and in-person components. Reflecting on their great work with students, Toki said that there are “so many challenges happening in the world. But when we hear the high school students’ [and] young people’s voices, and when we see committed teachers and enthusiastic students, I feel so hopeful, and that’s why I cannot quit.”

Day One Workshop

Most of the afternoon of Day One was devoted to a workshop focusing on brainstorming and discussing ideas that came up during the morning sessions. The facilitators were Brennan Tierney, a Massachusetts public school civics teacher and development consultant with Back from the Brink, and Dr. Vincent Intondi, a nuclear disarmament expert at Cornell University. To open, Brennan led the group in quick paired dialogue in response to two prompts: The first was to share one thing that is resonating for you from the morning sessions. The second was to discuss whether anything from the morning session shifted or deepened your understanding of nuclear weapons or disarmament.

For the first activity, pairs of participants moved around the room, visiting six stations where they were invited to use sticky notes to respond to prompts on different dimensions of disarmament. The reason they were asked to go around in pairs, said Brennan, is to engage with the prompts “through a dialogical lens.” Once everyone was able to engage with each one of the prompts, participants reported on key themes that were emerging for them. Here are the prompts and some responses:

- What role can educators play in the disarmament movement? Here, the responses suggested that teachers could become “more open” to learning about the issue. And then in turn they could do more to “motivate” and “inspire” students as well as lead them in guided discussion that could help develop both “critical thinking skills” and “curiosity” about the topic.

- What ideas or questions do you have right now? One main idea dealt with creating international programs or programs connecting different schools so that teachers and students could encounter diverse perspectives and ideas on disarmament. This would mean both engaging with difference but also creating important connections.

- What is something you wish for to support your disarmament work? Responses here were brief and to the point, and all were the same: funding!

- What are challenges to introducing these resources or topics in school? Funding was again raised as a factor, but many included “the current political situation” as a major limitation. The other main challenge mentioned was “time.” This pertains to both “teacher capacity” and the difficulties of finding ways to fit disarmament into their already packed curricula.

- How have today’s sessions shifted or deepened your understanding of nuclear weapons or disarmament? Some responses affirmed the notion that “knowledge is power.” Another indicated that “there is a clear imperative to teach this subject” and a great need for “reaching students.” Making an optimistic observation, one response said that “there are more young people involved than you think would be out there.”

- What are you resonating with today? In response, one participant simply said, the “urgency” of disarmament. Another point was the importance of countering the deterrence argument for the maintaining of nuclear weapons.

During a brief discussion after the share back, Dr. Andrea Bartoli of the Soka Institute for Global Solutions made an interesting point about money and funding. Acknowledging that funding is important, he observed that for one of Daisaku Ikeda’s mentors, Tsunesaburo Makiguchi, money was scarce, but this did not deter him from implementing and advancing his educational pedagogy for the happiness of children, which has now grown into a field studied and applied by educators around the world . Ultimately, he added, “I don’t think we will win the nuclear disarmament game through the money side.” Rather, it will be won through our “capacity to mobilize, to understand, to explain, to speak, to inquire.”

Next, Dr. Intondi spoke about how a university trip to Hiroshima and Nagasaki convinced him of the need for nuclear disarmament. When he returned to the United States, he felt a personal commitment to the work of eliminating nuclear weapons, in his case to educating young people around the issue. In particular, he started to research African American perspectives on nuclear weapons. This is because he believes that all students need to be able to see themselves or people who they can relate to in history in order to become invested in any topic. He also discussed the ways that nuclear disarmament education must be interdisciplinary and explored how nuclear disarmament resources might be incorporated into many different classes. “There is no shortage of resources out there,” he said. “The problem is distribution.” Currently, his project at Cornell University is working to make these resources more accessible for teachers of a wide range of subjects, from history to sports to music.

For the concluding activity of the afternoon workshop participants were asked to either work in groups, or individually if they wished, to brainstorm ways that “you can integrate and bring” to education settings “what we’ve been talking about and the resources that have been provided so far.” After 30 minutes spent on this activity there was just time enough for a brief share-back session. One idea shared was to structure a lesson around the economic aspects of the issue and to help students think carefully about and discuss how we want to prioritize our spending, locally and globally. Another idea was to have groups of students research and represent one of the nine current nuclear-armed countries. They would be asked to both discuss what their nuclear posture should be under current conditions and then consider how disarmament would change that country’s international engagement. Finally some participants talked about integrating nuclear disarmament into programs such as Model UN and even into other standard courses such as foreign language. The idea is to look at disarmament in ways other than from the military angle, considering social justice, the environment, and more.

Day One Concluding Session

Day one then concluded with a presentation from youth activists Maria Udalova and Talia Wilcox, both of whom are with the organization Students for Nuclear Disarmament (SND). Udalova and Wilcox began by sharing their personal journeys into this work and what inspired them to get involved. Udalova said she had always been interested in environmental issues and climate change. At the same time, many of her family members died as a result of the Chernobyl disaster in 1986, making this issue “really personal and important” to her. Eventually, she met the founder of Students for Nuclear Disarmament, Rishi Gurudevan, and has since started a chapter at her high school, Brookline High in Massachusetts. Wilcox, on the other hand, had never heard of nuclear weapons as a young person, except for “the tiny textbook page about World War II” in high school. After coming to Tufts University, Wilcox had the opportunity to hear a presentation on nuclear weapons by Dr. Jim Walsh, a Senior Research Associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Security Studies Program. Deeply moved, Wilcox expressed interest in working with Dr. Walsh and has been working on the issue with him and others since then. For Wilcox, if we think about nuclear weapons from a human perspective, they are “immoral and should not exist.”

Udalova and Wilcox then introduced the work of SND, a national, nonpartisan, nonprofit organization dedicated to raising awareness among Gen-Z about the threat that nuclear weapons pose to humanity. Their focus is uniting young people in urging the U.S. government to pursue “common-sense policies for a world free of nuclear weapons.” Since their launch, SND has reached many students at high schools and universities across the U.S. and is currently active in about 13 schools. In addition to organizing local initiatives around rallies, helping to pass legislation, and organizing in-school activities, SND also does a lot of awareness raising through social media and educational virtual forums on topics such as deterrence theory.

Day Two Activities

Day Two Sessions

After a whole-group grounding and reflection activity, the day two sessions opened with a presentation by Molly McGinty of the International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War (IPPNW), who discussed the work of her organization as well as the importance of the hibakusha to the nuclear weapons abolition movement. Reflecting on the hibakusha she emphasized that their lived experiences are not just historical accounts, but urgent moral calls to action—particularly for young people, who must now carry forward their legacy. She also emphasized that disarmament education is not simply about transferring knowledge, but about creating interactive, human-centered learning spaces where students are empowered to become advocates for a nuclear-free future. She then showed two videos illustrating the power of stories to advance the cause of disarmament. The first video profiled Mary Dickson, a Downwinder, those oft-forgotten U.S. rural and Native peoples who lived near the Manhattan Project’s atom bomb testing sites who ultimately were discovered to have experienced severe health impacts such as cancers, thyroid disease, infertility, and sterility.* The second video profiled the hibakusha Setsuko Thurlow’s 2017 Nobel Peace Prize Acceptance Speech.

For the second morning session, The Ikeda Center’s Senior Peace Researcher Alexander Harang shared the story of the long peace and disarmament tradition in his native Norway. In his presentation, he emphasized the vital role that educators play in the disarmament movement by acting as both formal and informal peace workers, bridging activism, diplomacy, and public awareness. Drawing on personal history rooted in Norway’s deep peace tradition—where peace is considered a national identity—Prof. Harang emphasized that disarmament education is not limited to academic settings but is embedded in grassroots efforts, school outreach, and civil society action. He also highlighted how educators can empower communities by contextualizing nuclear disarmament within broader peace philosophy, such as that of Daisaku Ikeda, and by connecting local actions to global frameworks like the United Nations. Drawing on his experience in academia, activism, and NGO advisory roles, Harang emphasized that education is especially important to advancing nuclear abolition during those times when formal diplomatic processes, such as those relating to the Treaty on the Nonproliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), are stalled.

Day Two Workshop

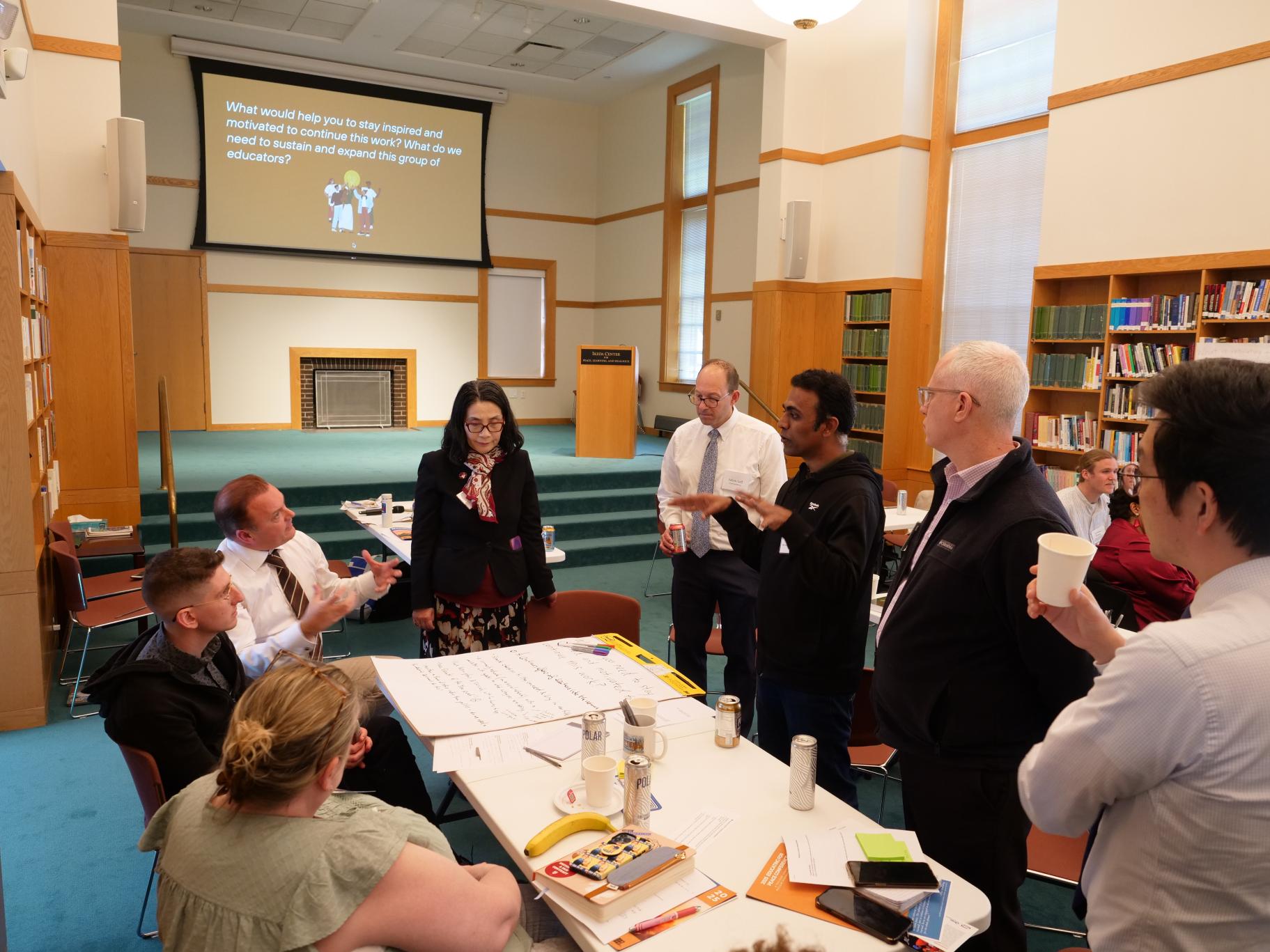

The Day Two workshop focused on applying ideas raised during the conference to educational settings. To begin, Brennan said they would pursue this goal by working on “two tracks.” One half of the participants would create a “student action plan,” considering questions like: How could you help students start a peace or disarmament club, or organize a day of action, or join or create a students for nuclear disarmament chapter? Participants in the second track would discuss ways to “integrate the lived experiences of atomic bomb survivors into their curriculum to humanize and deepen peace education and nuclear disarmament.” Also part of the discussion, said Brennan, would be to consider potential obstacles to implementation, instances of which he distributed to the groups on note cards.

After the two groups completed their discussions there was time for some whole-group share back. The main topic of discussion revolved around the obstacle or challenge of teaching such a difficult topic. As powerful as the stories of the survivors are, said one teacher, they can also be potentially triggering for students such as hers, many of whom come from backgrounds in which they experienced trauma, including as refugees from genocide. So what she does when teaching the stories of survivors, and also when teaching the horrors of Holocaust, is to keep a close eye on how students are responding, with the understanding that some students may have to step out. Day one presenter Kentaro Shintaku said that when he teaches the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki there often are students who feel overwhelmed and need to leave, adding that he always checks in with them. In one interesting case, he said, the father of a student who was struggling emotionally with the subject actually was appreciative, saying his son needed to learn about the real difficulties of the world. Ultimately, one reason that teaching this material is valuable, said SND’s Talia Wilcox, is that it teaches valuable lessons of empathy. One thing that is critical, she said, is always to leave students with a sense of hope, often by focusing on small, positive action steps they can take to make a difference. Citing examples of their peers who have made a difference is essential, she added.

The next activity of the workshop focused on the following question: How do we go from the vision of the world that we want to tangible action to make that happen? Participants then had 30 minutes or so to work in groups on their “vision to action” plans. The main topic discussed during share back was the importance of being able to pitch your ideas for disarmament education to decision-makers in schools and organizations. Joe Hodgkin of the Greater Boston Physicians for Social Responsibility (GBPSR), who works as a hospitalist at a local Boston hospital, said he could definitely see getting the go ahead to give a luncheon brown bag talk, for example, on the experience of the downwinder Mary Dickson, who suffered from thyroid cancer. That would fit well with the medical training model of considering case studies and would connect the core concerns of doctors to the disarmament movement. Another participant introduced a complexity to consider regarding the power of survivor testimony. Is it possible, she wondered, that two people could encounter such testimony and reach opposite conclusions, with one thinking this is the reason to disarm and the other thinking this is why we should commit to deterrence theory? Participants also discussed strategies for network building among teachers and students both within their schools and on a wider level. Attesting to the power of networks, one participant said being part of a network can really change your approach to teaching. This is because “there is safety there, and there’s help [and] motivation and it’s all premised on relationship.”

The workshop session concluded with participants engaging in paired dialogue on how they envision the future of the disarmament education movement. They then worked in small groups to brainstorm how to expand and develop this particular project. Ideas included: a continuous flow of educators into the network; Zoom conferences open to all interested teachers multiple times a year since it may be hard for everyone to gather in person; expanding and developing digital communications with updates on activities of members and lesson plans; and instituting a Peace Educator of the Year award. Maria Udalova also encouraged everyone to network with Students for Nuclear Disarmament.

Day Two Conclusion: Seeds of Action

To wrap up the day and the conference, everyone was given a note card on which they were invited to write down “one concrete action” that they would commit to doing in order to advance disarmament education. These were then displayed on a Seeds of Action wall. A few examples illustrate their commitments:

- I commit to incorporating peacebuilding activities/micro-lessons into my courses throughout the year but also to try to leverage peacebuilding skills and activities throughout our curriculum!

- My students will complete GBH’s youth media challenge in the fall of 2025 & we will share those publicly!

- I will connect one teacher to this network.

- One year from now The International School of San Francisco will have an active Student Group for the Disarmament of Nuclear Weapons — ready to grow!

- I will commit to engaging in dialogue with friends and family about what I learned at the conference and continue to educate myself on nuclear disarmament.

In closing, Kevin Maher expressed heartfelt gratitude for the meaningful and inspiring nature of the gathering, emphasizing how the openness, depth of dialogue, and spirit of collaboration far exceeded the organizers’ expectations. He also reflected on the deep significance of holding the event on Mother’s Day and during the 80th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

Building on this, Tetsushi Ogata reminded the group that just one year ago, a single individual’s vision led the Center to organize a panel on disarmament education—an effort that ultimately became the seed for this two-day conference. Moved by this growth, he highlighted the potential for lasting impact through collective action and envisioned a widening movement for engagement. He called for continued collaboration as part of a shared journey toward a more just and humane world.

* Source: The National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/mapr/learn/historyculture/downwinders.htm