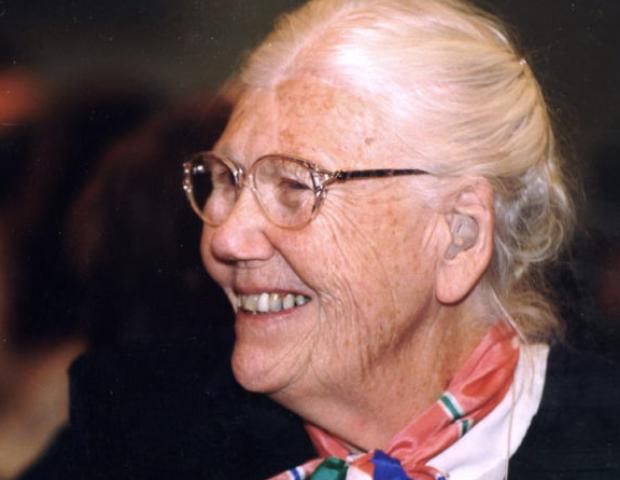

Elise Boulding: A Remembrance by Virginia Benson

The late Elise Boulding was known to many as “the matriarch of peace studies,” having developed the nation’s first peace studies program while a Professor of Sociology at Dartmouth College. To the Ikeda Center, Dr. Boulding was a great friend and powerful inspiration, having participated in many Center activities during the final 15 years of her life. The Center’s Virginia Benson composed this tribute not long after Dr. Boulding died in 2010.

During the fifteen years I knew Elise, from 1995 until she died in June of this year (2010), she was to me a peace mentor, a friend, and finally someone so close she seemed like family.

I met Elise in 1995, when she received the Center’s first Global Citizen Award. At the time she was still very sad to have out-lived her beloved husband and partner in peace, Kenneth Boulding. Nevertheless, she gave a talk full of conviction. Her tempered wisdom about community-building, cultures of peace, intergenerational connections, and the power of imagination touched our hearts and minds.

Only a year later she moved from Boulder, Colorado, to the Boston area to live with her daughter, Christie, commencing a new phase of what would be a very active state of retirement. My colleagues and I were overjoyed when we learned of her move. We quickly recruited this pioneer of peacebuilding to be our still young Center’s informal adviser.

The Center’s founder Daisaku Ikeda had admired the work of both Bouldings from afar for many years, exchanging books and thoughts with them through a correspondent. The resonance between his philosophy of peace and Elise Boulding’s was quite striking. Most basic was their shared belief that peace begins within the heart of the individual and radiates outward through relationships of every conceivable kind. As Elise put it, networking is peacebuilding.

In 1997, Elise became an enthusiastic participant in our events program. In her first activity with us, she joined a gathering of women leaders to discuss an early draft of the Earth Charter, an international statement of principles for sustainable living. (1) Lending her long view of time to this effort, she wrote in an introduction to the resulting book, Women’s Views on the Earth Charter, “The journey from the UN Charter to the Earth Charter has been an extraordinary half-century odyssey of growing awareness about the nature of human society and its relationship to the earth community.” Looking forward, she challenged us, “The task now is to open ourselves to change beyond what we can easily imagine.” (2)

Intrigued by Elise’s thinking, we decided to interview her for our fall newsletter that same year. (3) I remember being impressed by her insight into the relational quality of peace cultures. She reasoned that truly mutual “power with” relationships rather than hierarchical “power-over” relationships develop between individuals who can strike the “right balance” between two basic human impulses that create social tension—the need for autonomy and the need for bonding.

To Elise, building a culture of peace meant developing individual and social capacity for such balancing, so that the need of certain groups or individuals for autonomy would not have to “express itself violently.” In a culture of peace, people don’t suppress or eliminate conflict or difference. Rather, they deal creatively with the conflicts and differences that arise naturally in everyday life. Such cultures, she said, create secure space for individuality and generate “the kinds of behaviors that bring an end to injustice and war.”

Though Elise devoted much scholarly effort to elaborating the concept of peace culture, she was always careful to acknowledge the value of other peace perspectives. “This [educational and cultural] approach to the process does not for a minute diminish the importance of working directly on disarmament and the many strategies for conflict resolution and peace-making. It is simply an additional approach at a different level.” (4)

Taking action on this conviction, she soon proposed her own idea for a Center activity: that we host a series of seminars chaired by her and Dr. Randall Forsberg, founder of the Institute for Defense and Disarmament Studies. The aim would be to explore the differences and synergies between their two approaches to peace, one focusing on educational and cultural processes and the other on military and security strategies. For the better part of 1998 we hosted this series of gatherings involving local friends and colleagues. Later that year, we published the discussions led by these two outstanding female scholar/activists in a volume entitled Abolishing War. The book quickly found its way into the syllabi of various college courses on peace studies.

The momentum of our collaboration with Elise reached a peak in the spring of 1999 when we engaged her as co-convener with Tufts University sociology professor Paul Joseph for a three-part series of conferences at the Center entitled “From War Culture to Cultures of Peace: Challenges for Civil Society.” Together we created a unique learning experience for the Center’s community that even included a parallel “peace camp” for the children of participants.

These three weekend conferences examined in detail the transformations needed in family life and education, the global marketplace, and religious communities, if we are to achieve true cultures of peace. (5) Excited that we had found a way to include children in our deliberations, Elise led them in a peace camp exercise imagining a “nonviolent and fair world” ten years in the future. In an essay praising their responses, Elise wrote, “The campers made it very clear in words and in the pictures they drew that this would be a green world with no hunger, homelessness, or pollution—a world in which the sun shines for everyone. Sharing was a striking theme.” She recommended that the conveners of future peace-related conferences consider giving adults a similar chance to “spend time doing some deep listening to the children.” (6)

During these years, Elise was hard at work writing her final magnum opus, Cultures of Peace: The Hidden Side of History. In a conversation we had many years later, Elise explained the essence of her motivation, “Most people thought of peace as somewhere other than where they lived, and war as over there, and government somewhere else. But, I saw that peace-making is woven into every aspect of our lives. I felt this was a very important book to write.” (7)

When Elise’s book came out in the spring of 2000, we held a big celebration at the Center. One of the speakers, former US Ambassador to Austria Swanee Hunt, expressed her appreciation for Elise’s bold vision of peace—a direct and steadfast challenge to the culture of war. To underline her point, Ambassador Hunt told an evocative story from war-torn Yugoslavia. She recalled an 80-year-old woman named Sophia who lived in Croatia, noting that Sophia had “one job she cherished.” Every day at noon she would walk down to the town square, enter the church, go up into the steeple, unwrap the ropes, and ring the bell. One day, she went down to the church and found the steeple had been toppled and smashed in the fighting. The old bell lay on the ground in the midst of the wreckage. Undeterred, Sophia leaned over and grasped the clapper with her gnarled hands. Swinging her arms like ropes, she rang the bell with all her might. From that day forward, right at noon every day, Sophia could be seen loudly ringing that fallen bell. Turning to Elise, Swanee Hunt said, “And that’s our job, isn’t it, Elise?” You insist that we keep on “ringing the bell.” (8)

After the attacks on the World Trade Center the following year and the launch of the Bush Administration’s “war on terrorism,” Elise kept on ringing that bell. In August of 2002, we engaged her in a post-9/11 conversation to update Abolishing War, her dialogue with Randall Forsberg. When asked about “moral numbing” in the US due to the “war on terrorism,” Elise patiently but tenaciously responded, “What we have to do is to clarify all the values of democracy that we think we stand for, and show that when these violent social movements—which is the way I would describe what’s going on rather than use the term ‘terrorism’—when they come up, the way to deal with them is to address the causes that have led to the violence, to speak to the issues. Again, we’re moving in exactly the opposite direction by cutting back on our education budget and our human services budget and expanding the military budget, getting ready for outer space warfare. We’re acting like hegemonic terrorists.” (9)

By this time, Elise was living in a retirement home in Needham where she had moved in 2000. During those years, until she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2007, she gradually slowed the pace of her activities to match the limits aging had imposed on her physical stamina. And yet, she creatively challenged her circumstances. She found a way to continue lending her voice and her ear to the many local peace groups she supported, with generous friends ferrying her here and there. I remember Elise during this time as being hands down the most enthusiastic audience member we had ever hosted at Center events. It didn’t matter whether she spoke or just listened, she was always in her element at peace activities.

In 2004, knowing of Elise’s health restrictions and her wish to remain active in peacework, Center founder Daisaku Ikeda proposed they co-author a dialogue book together. He wanted to share her “frankly expressed philosophy and pacifist message to people all over the world.” (10) And all of this could be accomplished without Elise having to set foot outside her door. She was delighted. Questions and answers were exchanged between them in a series of interviews conducted during 2004 and 2005. When it came to editing the resulting manuscript, Elise’s work was sharp and assiduous.

Soon, the serialized version of her dialogue with Mr. Ikeda, carried in a Soka Gakkai International (SGI) periodical, became the topic for discussion meetings among women Soka Gakkai members in Japan. These Buddhist women, many housewives among them, were deeply inspired by Elise’s idea that raising children as peacemakers is in itself an extremely important form of peacework. A current of mutual inspiration already existed between Elise and these women. Twenty years earlier, in 1984, Elise had conducted research on women and peace during a visit to Japan. At that time, she had met with Soka Gakkai women and been inspired by a series of wartime recollections they had collected and compiled as volunteers. (11)

In 2009 when the Ikeda Center launched a new publishing arm, Dialogue Path Press, one of our first undertakings was to release the English version of the Boulding-Ikeda dialogue book, which we titled Into Full Flower: Making Peace Cultures Happen. When I finally had a chance to read this exchange now that it was in English, I was impressed. Mr. Ikeda had gleaned through reflective, long-distance conversation much of Elise’s wisdom about peace that had escaped my first-hand notice.

My most memorable moments with Elise had been when we talked about life.

Virginia Benson

His phrase, “frankly expressed philosophy,” is probably the best description of the book’s contents. And yet, philosophy wasn’t even what I thought of when I thought of Elise. Her disciplines, in my compartmentalized mind, were sociology, women’s studies, futures, and peace studies. In fact, she had played a key role in the founding of the latter three disciplines. With this thinking, though, I had missed that my most memorable moments with Elise had been when we talked about life. She had a rich, highly developed life philosophy. And Mr. Ikeda was determined to transmit its essence globally to the next generation of peacemakers wherever they may be.

At several points in the book he asked her for a “message” to youthful successors, and she responded forthrightly with strong conviction. For example, when asked what advice she would offer young people in their journey to create a better world, Elise said, “First, they must be able to conceive of a world without armies. Then they must start figuring out ways to make such a world happen. Although many people find the idea unimaginable, we must first have a mental picture of a highly diverse world functioning without military establishments and dealing creatively with conflict. My husband said over and over again, ‘What exists is possible.’ Think of all the places in the world where people do live in peace! A really good, working system is both possible and achievable.” (12)

Near the end of the book, Mr. Ikeda asked again for a message to youth working for peace, and Elise crystallized the essence of another concept she had pioneered, “I think in terms of what I call the two-hundred-year present when considering ways in which humanity can approach the ideal of being true global citizens. The two hundred years consist of the century that has passed since the birth of people who are one hundred today and the century that will pass before infants born today are centenarians. We have and will come into contact with people living through those two centuries across the planet. Each person from the oldest to the youngest is part of a greater community. Our contact with them means that we do not live in the present only. If the present moment were all, its occurrences would crush us. But if we think of ourselves as existing in a greater span of time—the two-hundred-year present—what a multitude of partners each of us will have in our particular lifetime, from youth to old age!” (13)

Reading these and other such comments elicited by Mr. Ikeda’s warm curiosity, I determined to listen more intently with a bigger heart to what Elise might have left to say. Even though she had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2007, still she was doing her best to see her condition in a positive light. Thanks in no small part to the beneficial influence of her son, Russell, she had realized that this was her chance to live fully in the present moment—to explore “being” itself. (14)

Having only the rough manuscript of her dialogue with Mr. Ikeda to help me learn more deeply from Elise at this stage of her life, I would bring it along on my nursing home visits. After reading an exchange, I would get her to reminisce. These exchanges reminded us both that she had already lived an immensely valuable life. She was surprised and pleased by her own insights in the book. I began to bring along my notebook and record the spontaneous thoughts that came to her after this bit of pump-priming. I soon realized that as facts and figures receded from her memory, her essential philosophy of peace was flowing powerfully to the surface. In a profound sense, her mind was now entering “full flower.”

My conversations with her during this period were loving, emotional, and deeply philosophical. Here are just a few of the things she said:

- “For whatever energy I have left, I want to use it in a positive way. I’m here in a way of loving the world. If we were all here in a spirit of loving the world, we’d have a very different world—all living things making room for each other.” (15)

- “We have a lot to teach each other. It’s all about the now. And for the moment, it’s fulfillment of that moment that counts… That’s one thing about getting old. You can’t get any younger!” She laughed. “You’ve learned the things you’ve learned. You do the things you need to do. You have to be the fulfillment of what you’ve learned. If you don’t, your life is incomplete. Don’t stop. Enjoy what you’re doing. Peace is about being and doing. It’s the happiest thing in the world you can do.”

- About the subtitle of Into Full Flower, she said, “That’s why we’re here, you know, to make peace cultures happen. That’s why we’re born. They don’t just happen. We have to make them happen. We do it together. We can’t make peace alone. That would be odd and lonely…just to sit around and ‘be peaceful.’ … Most people don’t understand that these special bonds that come from making peace cultures together are the most important thing in life.” (16)

At the very end, Elise had an overflowing love of nature. And this love emerged in poetic form. I would take her outdoors and just listen, writing down what she said. Her greatest joy came from looking up at the treetops from her recliner. I had always thought of Kenneth as the poetic one, because of his prolific writing of sonnets. But, Mr. Ikeda had opened my eyes to Elise’s poetry when he praised the poetic quality of her image of trees as joyful networkers and community-builders. She said in Into Full Flower, “When I compare humans and trees, it seems to me that trees stand on their heads, so to speak. Their roots, which absorb information and food, go deep into the ground, while their branches point up to the sky. It could be said that trees talk to one another root to root, while their legs dance in the air!” (17)

Later, living in a nursing home with a window by her bed, she gave new meaning to that poetic image. Though her body was now confined, her expansive spirit joined the trees “dancing in the sky.” On May 28, 2010, sitting with me on the patio less than a month before she died, Elise recited effortlessly a final, joyous ode to the trees, the “now,” and her love of networking:

Everything is in the now.

The trees and the sky

And you and I

We’re in the now!

See the wind dancing in the trees.

Or is it the trees dancing in the wind?

Trees can’t dance without the wind

The wind can’t dance without the trees.

We all need each other

And I need you

And you need me.

So happy

I could lie here forever

But I won’t

I’m heavenward seeking.

For me, this is the perfect place

I could live up in the top of that tree

I can send myself up there on the top.

Now, I’m waving in the wind.

Everything needs everything. (18)

Elise’s last poem, a beautiful fulfillment in itself, also brings to mind a prediction for humanity’s future that she made near the end of Into Full Flower: “But we humans can and will learn to live together as a family on this planet. There is a spirit in each of us that will make this possible. First, though, we must learn to listen to that spirit and to listen to one another.” (19) Strong encouragement indeed from a noble peace pioneer who kept on ringing that bell to the end of her days.

— Virginia Benson, September 17, 2010

Notes

1. For more information on the Earth Charter, go here.

2. Women’s Views on the Earth Charter (Cambridge, MA: Boston Research Center for the 21st Century, 1997), pp. 7,9.

3. Boston Research Center for the 21st Century (BRC) Newsletter, No. 9, Fall 1997, pp. 8-11.

4. Ibid.

5. For Boulding’s keynote address at the first conference, go here.

6. BRC Newsletter, No. 13, Spring/Summer 1999, pp. 8-9 (currently unavailable on the Center’s website).

7. For notes on this conversation see the “May 9 Visit” link in the entry for Thursday, October 7, 2010, at http://www.earthenergyhealing.org/EliseBoulding3.htm.

8. See BRC Newsletter, No. 16, p. 10.

9. See “A Conversation with Elise Boulding and Randall Forsberg”

10. Elise Boulding and Daisaku Ikeda, Into Full Flower: Making Peace Cultures Happen (Cambridge: MA, Dialogue Path Press, 2010), pp. 1-2.

11. Ibid., p. 68. Selected English translations of the full series of recollections were published in 1986 by Kondansha International as Women Against War.

12. Ibid., p. 30.

13. Ibid., pp. 112-113.

14. See “Elise Boulding’s Journey with Alzheimer’s,” a website chronology created by Russell Boulding, http://www.earthenergyhealing.org/EliseBoulding3.htm.

15. See “Ginny Benson’s Conversation on May 13, 2009” under “Index to postings” at http://www.earthenergyhealing.org/EliseBoulding3.htm#Index.

16. For notes on this conversation see the the “May 6 Visit” link in the entry for Thursday, October 7, 2010, at http://www.earthenergyhealing.org/EliseBoulding3.htm.

17. Into Full Flower, p. 27.

18. For notes on this conversation see the “May 11 - June 23” link in the entry for Thursday, October 7, 2010, at http://www.earthenergyhealing.org/EliseBoulding3.htm.

19. Into Full Flower, pp. 103-104.